Tori and I went to an estate sale this morning, and it just made us sad.

An estate sale is distinct from a yard sale. A yard sale is people trying to make a few bucks by selling their crap to people who say, “Hey! I’ve been looking all over for crap like this! I could really use this crap!” An estate sale, on the other hand, is usually about the family trying to empty mom and dad’s home of a lifetime of accumulated things so they can sell the house.

And estate sales usually have a story. Sometimes the story is about the couples’ travels around the world, or their love of golf, or photography, or gardening or fishing. A life spent painting, or a career aboard working ships. There’s a story, and the keepsakes, treasure and chachkas are usually laid out to show them to their best advantage. To tell the story.

Not so Saturday. We had been drawn by the photo on craigslist that showed a shelf of Toby jugs, including a pirate one. We are not collectors, but – you know – pirates.

We walked into the house in northern Metairie, a nice neighborhood, and into the saddest story I think I’ve ever seen. First of all, there was no order. I was instantly reminded of a reporter I had worked with who came back from interviewing an older woman and told us, “The knickknack shelves were choc-a-block with bric-a-brac.” Only this was far, far worse. It was chaos, accompanied by a smell that I can only call “little old lady funk.”

There were easily a thousand Styrofoam containers – maybe twice that many, it was impossible to count them all. Most were about eight inches square and an inch thick, many still sealed in the plastic they had been shipped in. They spilled from every closet, they were piled on every flat surface, formed small, sad mountains in the corners of every room in the squalid house. Each contained a “collectible” plate. There were series of sports stars (Mickey Mantle, Steve Young, Kordell Stewart,) birds (Orioles in the Summer, Robins in Flight.) There was a Japanese series of kimono clad geishas. Religious themes, a series of sunsets. Children praying.

There were easily a thousand Styrofoam containers – maybe twice that many, it was impossible to count them all. Most were about eight inches square and an inch thick, many still sealed in the plastic they had been shipped in. They spilled from every closet, they were piled on every flat surface, formed small, sad mountains in the corners of every room in the squalid house. Each contained a “collectible” plate. There were series of sports stars (Mickey Mantle, Steve Young, Kordell Stewart,) birds (Orioles in the Summer, Robins in Flight.) There was a Japanese series of kimono clad geishas. Religious themes, a series of sunsets. Children praying.

Closet shelves were swaybacked under the weight of them.

Most of them you had to guess at, because few had been catalogued or labeled or accounted for in any way. They had been delivered, and immediately put away. There were also dozens of those little ceramic, Victorian buildings, each with a little light in it, that you put together into a display of an old village – church, train station, etc. Except these had never been displayed. They were all in their containers, stashed away in closets.

Most of them you had to guess at, because few had been catalogued or labeled or accounted for in any way. They had been delivered, and immediately put away. There were also dozens of those little ceramic, Victorian buildings, each with a little light in it, that you put together into a display of an old village – church, train station, etc. Except these had never been displayed. They were all in their containers, stashed away in closets.

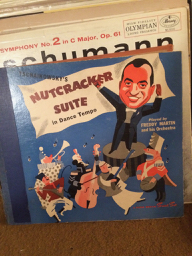

There were a few books, none less than 30 years old, copies of Life and Look magazine (both of which have been out of circulations since the early ’70s,) record albums – 33s and 78s – including one that caught my horrified attention, “Tschaikowsky’s Nutcracker Suite in Dance Tempo,” by Freddy Martin and his Orchestra. Thank god it was a 78 or I’d have been tempted, even though I don’t own a turntable.

In the kitchen there was a mass of dishware and appliances, all of it old. For instance, there was what I took to be the base of a blender that must have been 50 years old. A woman plugged in a coffee pot to see if it worked. It started smoking. She bought it anyway.

There was little in the way or clothing or personal items. No men’s clothing. A couple of canes hung over a door, they were noticeably short.

There was little in the way or clothing or personal items. No men’s clothing. A couple of canes hung over a door, they were noticeably short.

On one wall were proudly hung three well-framed diplomas. I had gleaned from the packing materials of the plates that the woman’s first initial was A, her husband’s was D. These diplomas – bachelor’s degree, masters, and doctorate, all in engineering – were all to someone whose first name was James, almost certainly a son. There was no other sign of a son in the home. Maybe he’d already gone through and taken anything of sentimental value, but why would he have left his diplomas?

The story that emerged was of a woman whose husband had died some 30 years ago or more, who had lost contact with her son – either he had died or tired of his mother’s obsession. Her life revolved around these collectible plates. Not for their aesthetic value. The few actually on display on the wall were of Native American motifs and were nothing special. Each day that the mailman delivered a package from W.S. George Fine China or some other such purveyor was a special day for her. She lived for it. Some of these packages she opened, but most she cherished just “having” them and put them away wherever they’d fit. Even the ones she opened to look at were put back into their containers and stored.

The story that emerged was of a woman whose husband had died some 30 years ago or more, who had lost contact with her son – either he had died or tired of his mother’s obsession. Her life revolved around these collectible plates. Not for their aesthetic value. The few actually on display on the wall were of Native American motifs and were nothing special. Each day that the mailman delivered a package from W.S. George Fine China or some other such purveyor was a special day for her. She lived for it. Some of these packages she opened, but most she cherished just “having” them and put them away wherever they’d fit. Even the ones she opened to look at were put back into their containers and stored.

It wasn’t a collection. It was a hoard. And it was sad.

A quick online check confirmed that these plates had only slight economic value – a website for similar objects was asking $16 a plate, and what you ask and what you actually can get are two different things. There were two guys working the sale for one of those estate sale companies, and the one we talked to was very stoned. I said to Tori that if we were different people we would offer the stoned one, say, 50 cents or a buck a plate, walked away with a couple of hundred, then catalogued them, put ’em online for five bucks a pop, and made a little money. But before I could even add the obvious she said it for me. “We’re not those people.” No. We’re not.

Netflix tidiness star Marie Kondo would have been horrified. She would have thrown up her hands and run shrieking. This wasn’t a space that needed blessing or thanking. It needed a flame thrower.

Netflix tidiness star Marie Kondo would have been horrified. She would have thrown up her hands and run shrieking. This wasn’t a space that needed blessing or thanking. It needed a flame thrower.

We did buy something – a book (a collection of Alexander Woolcott’s writing from the early New Yorker that I was happy to get for $2,) and a 1968 Life Magazine (that I remembered from school) containing an unpublished/unfinished Mark Twain manuscript, for a buck. There were a couple of the Toby jugs left, but the pirate was long gone, so we left those alone.

And we made ourselves a promise. As soon as we got home, we were going to throw something away. Anything. Because, damn!

And now I need a shower. To wash the sadness off.